<Click here to see the blog post in International Sign>

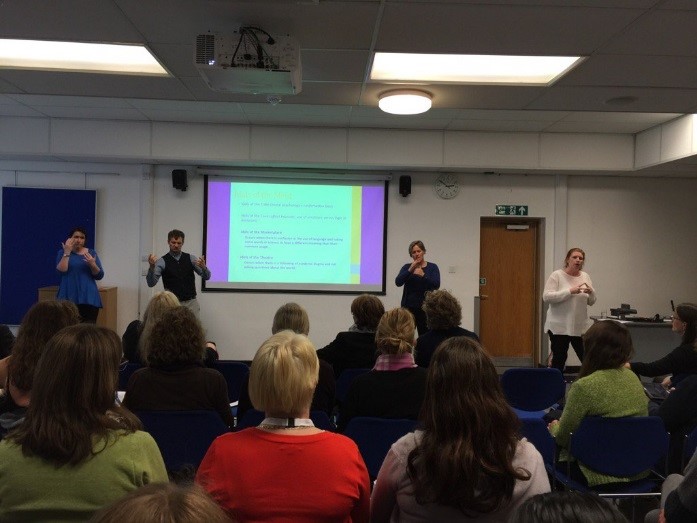

Recently I went to Australia as I had been invited as a keynote speaker at the International Federation of Translators & Interpreters (FIT) world congress in Brisbane. This was a historic moment at the FIT congress, as it was the first time they had experienced a keynote presentation on the topic of sign language interpreting. The fact that I chose to deliver the keynote address in Auslan (Australian Sign Language) also made a greater impact on the audience as I discussed the importance of recognizing signed languages as real languages on a par with spoken languages. Through my presentation I dispelled various myths about signed languages and confirmed for many reasons why signed languages should be considered as equal to spoken languages.

The congress was attended by over 800 delegates from all over the world representing a vast array of spoken languages, and the delegation was made up of translator and interpreter practitioners, educators and researchers. There were also approximately 20-30 (deaf & hearing) Auslan/English interpreter members of the Australian Sign Language Interpreters Association (ASLIA) present at the conference.

At the end of the congress, each of the keynote speakers was asked to summarise their experience of the conference and present any key highlights or themes we felt that were worthy of note. I noticed one theme that was embedded within, and pervaded all, the presentations that I saw throughout the conference. This was the theme of ‘power’. For example, in one presentation about the Australian Aboriginal Interpreting Service, the importance of family connections was discussed and how hard it can be to navigate interpreted interaction when your interpreter is a family member, and the potential disempowerment Aboriginal Australians may experience when family members also have to interpret for them. Power dynamics were explored in relation to medical interpreting, and how interpreters’ decision-making can impact on the rapport between doctors and patients. Similarly, interpreters are in a powerful position in police interpreting, when their interpreting decisions can have a significant impact on people’s lives.

As I have already mentioned, in my own keynote address I discussed various issues in relation to signed languages, and it occurred to me that the theme of power was also evident in my own presentation – in the fact that I chose to present in Auslan. I could make that choice. This is about power of language choice. Many of the (spoken and signed language) users that translators and interpreters work with do not have that choice, therefore they do not have that same level of power. As a hearing person, I am in an immensely privileged position to be able to make that language choice: to choose one day to present in Auslan, and the next day I could present in spoken English. My language choice can also be determined by who the interpreter might be that is interpreting for me from Auslan into English, and whether I feel comfortable with them ‘being my voice’ or whether I would rather speak for myself. Many of my deaf friends and colleagues don’t have that choice. They don’t have the power that I have.

This issue links with a previous research project I have been involved in – the Translating the Deaf Self project – which examined whether deaf people feel that they are ‘known’ by hearing people through translation, i.e., do they feel represented by interpreters. Many of the deaf participants in our study reported that they felt that they have little choice when it comes to working with interpreters, and face challenges and barriers to feeling like they are adequately represented. (A full copy of the research report is available if you would like more detail: email j.napier@hw.ac.uk).

So this experience has made me further reflect on my position: who I am; and how important it is to acknowledge one’s positionality as a researcher (see Young & Temple, 2014; Napier & Leeson, 2016; Kusters et al, 2017). I was invited to be a keynote speaker at the FIT Congress as a result of my international profile as a sign language interpreting researcher. But ultimately I was a hearing person talking about signed languages. I chose to present in sign language, and the fact that I did that did make an impact on the FIT congress audience, as it brought into evidence – ‘made real’ – many of the issues I was talking about. But we need to see more opportunities for deaf people to talk about their language and their experiences as deaf sign language users.

I thoroughly enjoyed the FIT Congress. It was a wonderful experience, and I felt very honoured to have been invited. It was an important event for FIT in having the first keynote about sign language and sign language interpreting, so I recognise and respect that. But at the same time, my attendance and presentation at that congress has made me think about my work; my language choices; my power. So I decided to write this blog to acknowledge more widely that I recognise this privilege; this power. It’s made me think about my future attendance at conferences; my language choices; who I want to have an impact on through my presentations; and whether deaf people are involved. This is something that I felt important to share through this blogpost.